Resistance and Repression in 1919 Korea [Joa]

March 1st Movement

This project explores how location of one’s participation in demonstrations during the March First Movement (1919) in Korea affected interactions with Japanese repression. This series of mass demonstrations across the country witnessed the Korean populace protesting Japanese hegemony since the end of the Choson Dynasty (1392-1910). Historical literature has noted the breadth of the movement and the severity of the Japanese response. Indeed, it is an event that continues to resonate in collective Korean memory.

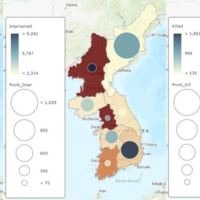

My unit of analysis is a province according to Choson Dynasty arrangements, comprising a total of eight provinces. While location can take on a number of scales and forms—for example, village, city, province, country—I focus my analysis at the provincial level largely because it is the smallest unit of comparison for which data is available. This data includes the number of demonstrations, participants, and major demonstration sites, defined as locales with more than fifteen demonstrations or where participants totaled over 10,000. Regarding forms of repression, I look at four main variables: the number of demonstrators per province who were (1) arrested, (2) imprisoned, (3) wounded, and (4) killed.

Significance

The first map illustrates contours of Korean resistance—namely, where there were the largest numbers of protest sites and demonstrations, as well as the highest participant ratios. The visualization of this data makes clear that Pyongan Province and Kyonggi Province experienced the greatest Korean resistance by all three measures. Nonetheless, there were also substantial numbers of demonstrations in the southern provinces (large circles). Their significantly larger populations, however, can perhaps explain their relatively smaller participant ratios. Kyongsang Province, for instance, has twice the population of Kyonggi Province. Meanwhile, Hamgyong Province and Kangwon Province, located in central- and north-eastern Korea, respectively, may have the lowest number of demonstrations (small circles) because these are mountainous regions. Indeed, almost all the major demonstration sites are located in the west.

The second map provides a means to understanding the contours of repression. These maps reveal two patterns in particular. First, the areas with the greatest arrests are also those with the greatest imprisonments. Second, Kyongsang Province was hit hardest by repression, which may in part be due to its proximity to the Japanese mainland. Among other peculiarities, the maps reveal that Hamgyong Province, in northeastern Korea, witnessed a significant amount of arrests and imprisonments despite relatively low resistance. A possible explanation is that, from the Japanese perspective, a smaller number of demonstrations and participants is easier to control. These maps also show that, in general, participants across the country were more likely to be arrested or imprisoned rather than wounded or killed.